“Death, dying, and grieving today have become unbalanced. Health care is now the context in which many encounter death and as families and communities have been pushed to the margins, their familiarity and confidence in supporting death, dying, and grieving has diminished. Relationships and networks are being replaced by professionals and protocols.” (The Lancet Commission on the Value of Death, 2022)

Death is the only life experience, other than birth, that every one of us will experience personally. Yet many of us find it difficult to talk about death. Because of this, some people are unprepared when death approaches; this lack of preparation can itself cause greater suffering. Without awareness, there may not be time to say goodbye to those we love; without wills, assets can become contested and tied up in probate; without advance care directives, people may receive medical interventions they don’t want to have.

To learn more about what concerns and preferences people have regarding the end of life we designed a pilot project to explore these questions. Our thesis was that if people have the opportunity to talk about eventual death in a safe environment without the emotions and fatigue that often come with imminent death, they will be able to prepare better for death when it does come. The aims of the project were to:

- explore people’s concerns about suffering, in the context of dying and death.

- pilot a methodology that encourages people to discuss what is meaningful to them in relation to the end of life.

This paper presents the full findings of our research; early findings from round 1 were presented in an Insights paper published on this website in November 2022.

Methodology

We began a snowball sample with people who were known to us and asked them to bring together people with whom they would be comfortable having a conversation about dying and death. The lead contact then invited a group of up to four individuals to meet together in a familiar and safe setting; this was usually someone’s house. Interviews were also conducted in a café, a park, and an office. Food was almost always involved.

Potential participants were provided with an invitation outlining the research, stressing that participation was voluntary. People who agreed to participate were then provided with an information flyer and a consent form. Consent was reaffirmed at the time of the meeting. Interviews were conducted in confidence using a tailored interview guide and recorded and transcribed for analysis purposes. Afterwards, participants were provided with a self-care guide in case the discussion had brought up any distress, including the opportunity to debrief if desired. Participants were also contacted the next day, and a suite of information and resources on advance care directives and end-of-life planning was provided by email.

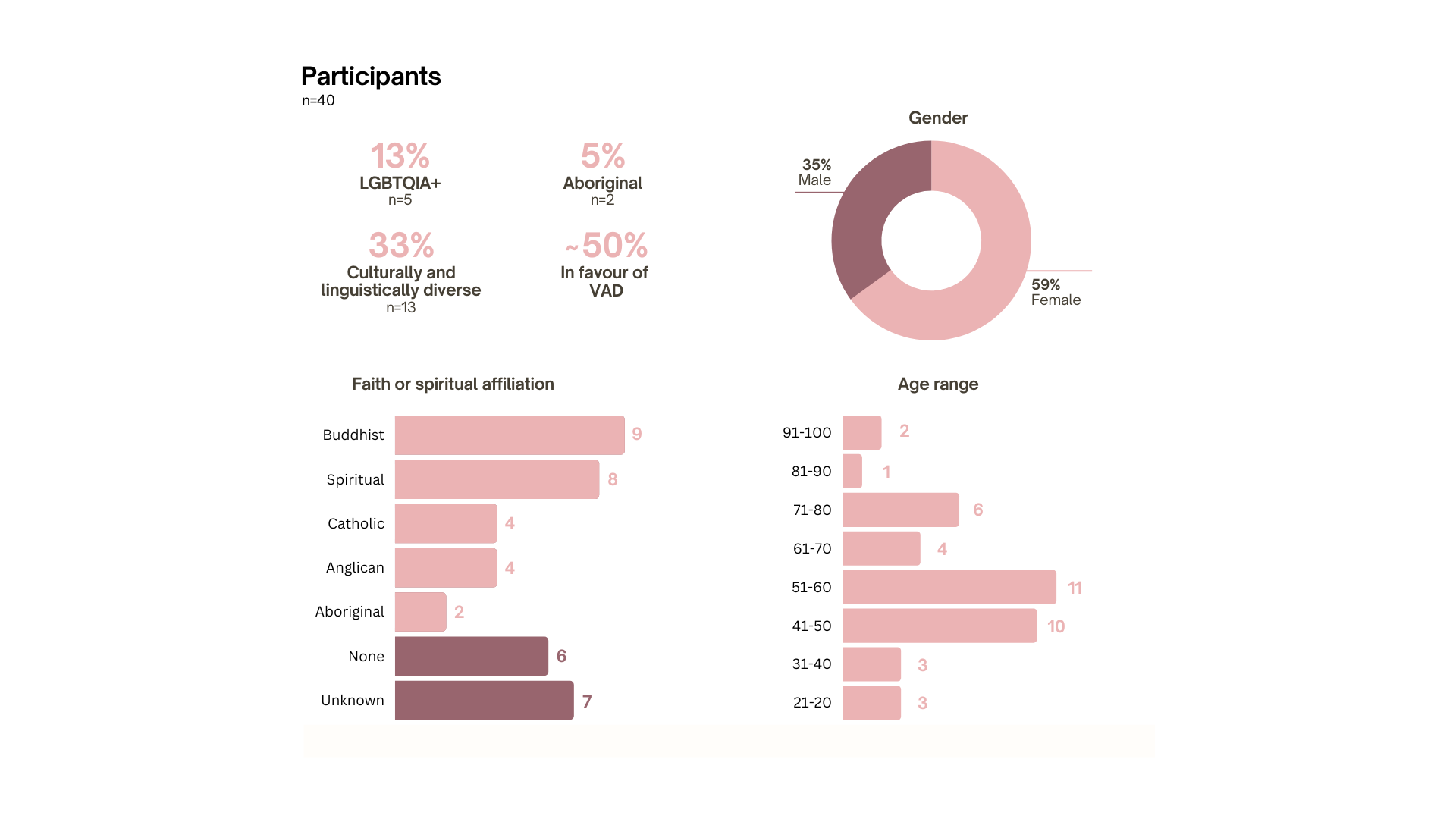

Seventeen single or group interviews were conducted with a total of 40 participants. Interviews lasted for up to 90 minutes. The demographic details of the participants are outlined below.

As a qualitative study these findings are not representative of the larger population. Rather, this research provides a snapshot into the variety of experiences of 40 people with different life stories, histories, and beliefs. The one unifying theme that emerged clearly from all discussions was the significant impact of love and relationship in the end-of-life experience.

Four general themes arose from the conversations, which are discussed below.

Findings

Death is a social process

Many participants expressed a primary concern about relationships: about the emotional impact of their death on loved ones, about grief (their own or others), about being able to be with people they love at the end, and about being able to say goodbye, express love or make right things they have done.

“One aspect of my own death that causes me great sadness - not fear of my death - but sadness of the thought of leaving my grandchildren, more so than my grown children, I would hope to live to a sufficient old age so that my grandchildren would be mature enough to accept the death of their granny.” (Female, 70s)

A number of people told stories of how their relationship with a dying person was illuminated by the experience of being present at the time of death. For several who had what one person called ‘the privilege of sharing this time’ with a loved one, there was often a powerful experience of love which changed the bereaved one’s life.

“I believe that love and life, or life, love and death are very closely linked. There is not much separation in the two of those things, so to love you’ve got to die. I think that I was scared of love, not death, with my father.” (Male, 60s)

This was not to deny the distressing or even agonising aspects of the body’s decline. Indeed, several people acknowledged that it had been extremely challenging to be present and witness the physical and emotional suffering of parents or friends. In general, people’s concerns about pain and physical symptoms centred on the process of dying, rather than the death itself.

“The actual moment of death for most people is not so painful, that's not the issue, but it’s everything surrounding.” (Female, 30s)

Participants also worried about the impact of their death on others, such as children or grandchildren, and the ability of others to process the loss. This included making plans such as identifying in advance a preferred residential aged care facility, or telling other family members what wishes they had for their end of life, in order to take the burden of decision making from adult children. There was a recognition that the loss of one life had an intimate impact on those who were in relationship with that individual.

Those who had experienced the loss of a loved one tended to speak about death as a catalyst for understanding that each moment of life is precious.

“Staring death in the face and really being aware that you could die any moment kind of makes life a bit richer, you know, and so there are many benefits to talking about dying, some of which is to make life better right now, not just to make death better.” (Male, 40s)

There is a lack of emotional, social, community or bereavement support

Some people reported loving and deeply emotional experiences of spending time with loved ones as they died. For some people, family and formal support at the time of death and afterwards made the experience bearable and even ‘a gift’ that enriched their lives.

However, some participants who were also clinicians or care providers noted that there is sometimes little support available to debrief or talk through the emotional challenges of living with frequent exposure to death. For professional caregivers, their experiences provided a familiarity with the many guises of suffering and an ease in talking about death, but also an acknowledgement of the toll that caring can take. Care providers did tend to have clear ideas about what they wanted at the end of life. One participant, a former nurse, spoke about how important it was for her to wash the body of someone who had died, as a way of caring and providing dignity for that person even though they were no longer present in the body. She would like someone to provide that type of respectful care for her when the time comes.

Some people, particularly those who had some familiarity with the Australian health sector, acknowledged that their level of knowledge would help them to advocate for their needs. Others noted that they did not know where to find information about the support and services available.

In general, people were aware of palliative care as care at the end of life, but fewer people had direct experience of the formal palliative care sector. Participants spoke of their experiences in hospitals, of providing care at home with community (or no) support, or of supporting someone in an aged care facility. In some instances, the ambulance services provided the final care for the dying person. Sometimes the family needed greater support than the person who was dying.

“I think that having someone there more as a support for the person supporting the death is something that is missing. So it’s always on the other family [members] and staff, and sometimes like families aren’t good, so it’s a lot of pressure on those people who are sitting on the bedside.” (Female, 30s)

People expressed a desire to have information well in advance of when it was required, to encourage open conversations about preparing for the end of life. Several participants compared the process of birth with the process of death, noting that both were messy and painful but unavoidable. One person, a former midwife, noted that preparing in both cases can ease the process:

“You've either done the work beforehand or you haven't. ‘This is it, everyone, and I can't help you [prepare] anymore’… the work is psychological work, it has to happen [beforehand], then what happens in the moment is almost luck of the draw.” (Female, 60s)

People were influenced by the experience of others at the end of life

Many people used the experiences of others to learn about how to manage or respond to end-of-life needs, for instance recalling the stories of family or friends who had had to navigate the care sector for someone at the end of life. A few people related how they learned on the job about providing care for a family member.

“One of the nurses taught me a few things as well…I'd asked questions and a lovely nurse showed me a few things, getting him in and out of bed, so I didn't hurt my back basically.” (Male, 50s)

There was a general (and natural) desire to avoid the indignity of the body’s failings. Those who were in favour of VAD generally spoke of this option as a way of controlling the manner of their death and avoiding the indignities of the body’s decline. This was particularly true for people who had witnessed an agonizing or distressing death of someone close to them.

Conversely, those who had witnessed a peaceful death were less likely to be worried about the process of death or feel the need for VAD.

For many participants, the opportunity to spend time with the person who was dying was a important gift, one that changed their understanding of the place of death within life. As one person said, “he really gave a gift to people to be comfortable with talking about his own death, and doing that he would have made people comfortable with their own deaths too.” (Male, 40s)

This reinforced a common theme across all conversations, which is the importance of relationship. Death was not something to be experienced alone. One participant reflected on the value he found in talking openly with his friend about her impending death.

“I find every time is a good time to make meaning out of life, but the opportunity to have those chats is really useful…the time I spent with [my friend] every Sunday, for 15 months [before she died] was some of the best times of my life, because we had those chats.” (Male, 40s)

Spiritual beliefs can help people make sense of the place of death in life

Some participants had thought deeply about the meaning of life and death’s place in life. People who had a belief about the value of death as part of life expressed less fear or anxiety about how their death might occur and were generally comfortable in articulating what they would like at the end of life.

Some people were very clear that death is the end: there is no spiritual aspect of life or afterlife about which they are concerned. Life is what we have at the present and when we die that life is gone, extinguished. For people who held this belief, their expectations of the end of life tended to be very practical. “I want to go to sleep and don’t bother anybody just fall asleep and don’t wake up and that’s it.” (Female, 90s) Others wanted familiar faith rituals at the time of death and for their funeral or mourning period. “[I want to] surround myself as much as possible with Buddhist things, objects, mantras, teachings, Buddhist statues… you know prepare my mind to be in a more virtuous state.” (Female, 50s)

While dying at the end of a long life is expected as the natural course of events, witnessing a death at a younger age through illness, accident or suicide often had a significant impact on those who remained. Two participants who had contemplated suicide in the past noted the challenge of choosing to live. A few people spoke of near-death experiences and how that changed a person’s belief in what happened after death. One Aboriginal participant noted that death was familiar because so many people in his community died young; he himself had not expected to live into his 60s and had to revise his life plans accordingly. For these participants, proximity to death made them reconsider the value of life. Living to a great age also, for some, brought peace and an acceptance of death.

“We all talk about it, and we know that even if you don't talk about it, that you are born and eventually you will die, I mean that is inevitable.” (Female, 90s)

How conversations support end-of-life care

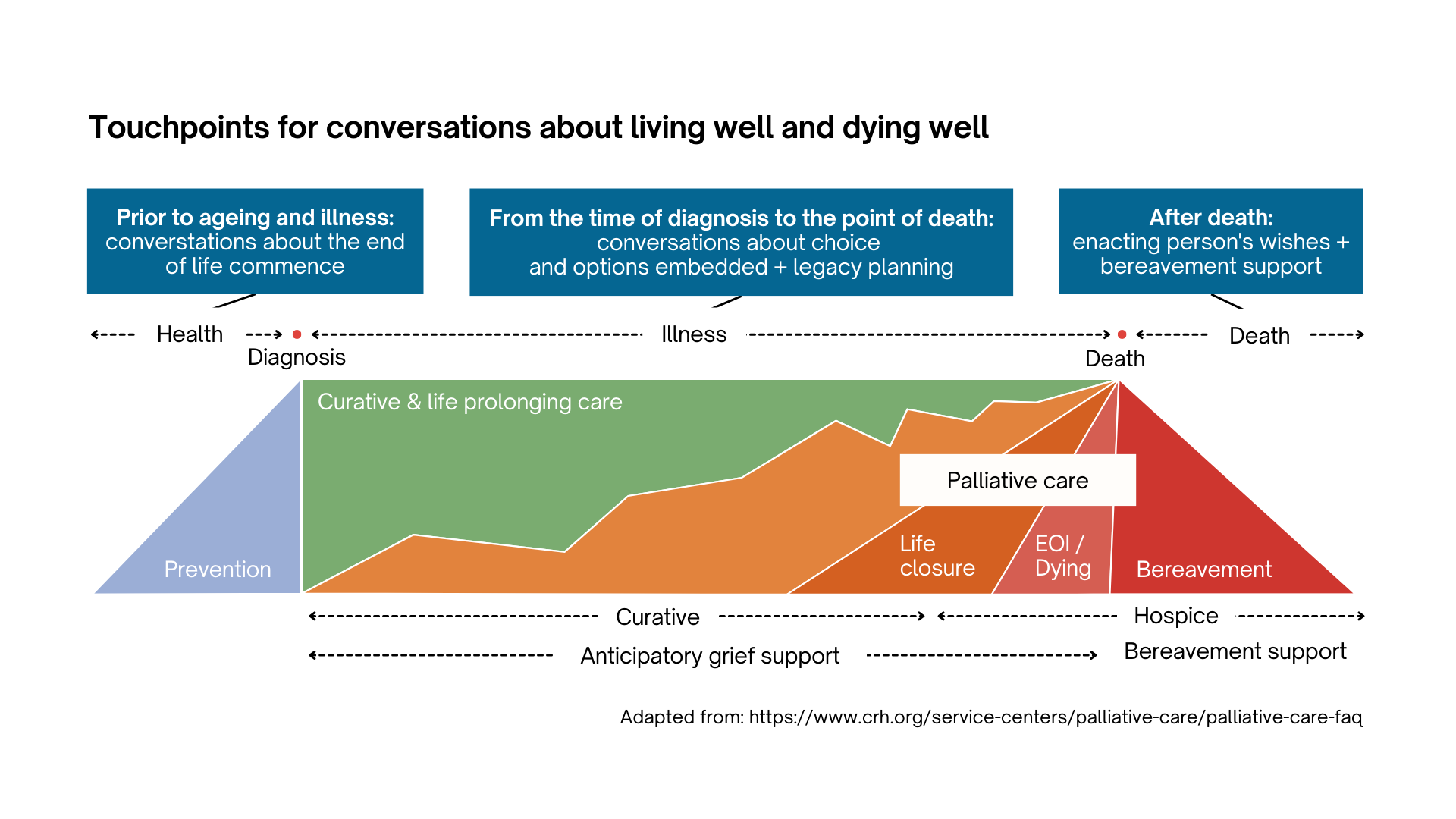

The focus groups demonstrated that there is no best time to have the conversation. However, the data also suggest that having the conversation before a life-limiting diagnosis, or a sudden death, can help prepare people by providing knowledge and information that will be needed when death does come.

The diagram below maps a timeline for talking about death, showing that this can start at any time and ideally should start well before a life-limiting diagnosis.

Impact

All participants considered that it was valuable to discuss their thoughts or plans for the end of life. Some participants noted that acknowledging the reality of death helped them to focus on living each day as fully as possible. Others noted that they felt better about the idea of death for having talked in the group. Some continued the conversation after the formal focus group conversation ended.

On 9-month follow-up of round 1 participants, approximately one-third had taken action as a result of participating, such as:

- consulting a death doula to learn more about the service

- speaking to family members to communicate personal wishes for the end of life

- deciding to attend a Dying to Know Day event

- deciding to complete paperwork like a will and/or writing down one’s wishes for the end of life.

Others were comfortable that they had already prepared and indicated that nothing had changed as a result of the conversation. Still others found the conversation useful in helping them to think about what they want, although they had not yet taken action.

Conclusion

The first goal of the Australian National Palliative Care Strategy is Understanding: people understand the benefits of palliative care, know where and how to access services, and are involved in decisions about their own care. It is the first goal because people are at the centre of good care at the end of life. Unless people know what care options are available, they won’t know what care is possible. Likewise, if people have not thought about what they want, they can’t ask for it. Every human is different and will have different needs and preferences for care. If these preferences have not been stated, or solicited by care providers, they are not likely to be met.

We need to embed conversations about living and dying well throughout the healthcare trajectory and our social discourse. Many organisations and health services have developed resources to help people think about what they want at the end of life. Resources alone are not enough, however. Normalising the reality of death in life can only be done through conversations between people in relationship, with care providers, and among care providers themselves.

This project has demonstrated that an intentional discussion on end-of-life wishes, facilitated by an experienced independent person and conducted among friends in an emotionally safe environment can help people to prepare for their own end of life or that of others. Talking among friends also helps people to know what others want, and builds support within relational networks.

In addition, participant responses suggest that while there are a number of resources to help people think about end-of-life care planning, these are not widely available. There appears to be a gap in the provision of practical information for informal carers and family members who are supporting someone at the end of life. It would be beneficial to create a resource such as a comprehensive guide book that is standardised for national or regional distribution and draws together existing resources in one place. Some respondents suggested this could be similar to the ‘blue book‘ commonly available for women at the time of birth.

There is an urgent need to increase informal social and emotional support for people who may be approaching the end of life. Developing local community initiatives to offer relational support to people facing the end of life and their families and carers may alleviate the fears many people expressed of being alone or not being able to care for a loved one. Some local councils, such as MidCoast NSW Council or Sutherland Shire Council have created events designed to bring people together and provide information on topics such as grief, legal issues, funerals and burials.

“Normalising death for people, helping people have these conversations…not just normalising it but making it, bringing a bit of humour in, or bringing a bit of lightness in is really important.” (Female, 50s)

We will all die. The ultimate aim is for each of us to live fully before the end finally does come. We can’t do this alone.

Linda Kurti

Stillpoint Strategy

0412 040 217

linda@stillpointstrategy.com.au

www.stillpointstrategy.com.au

Harpreet Kalsi-Smith

Kindness Company

0402 249 058

harp@kindness.company

https://kindness.company/

Image by Dominik Lange on Unsplash