November 2022

Recently, Stillpoint Strategy and Cox Inall Ridgeway collaborated on a qualitative study to examine how people make sense of life, death and suffering. We extend our thanks to all the participants involved in the research who gave generously of their time and insights.

In a series of focus groups and interviews, we spoke with 29 people of different ages, sexual orientation, religion and ethnicity, from metropolitan and regional locations.

All participants valued being invited to talk about such an important and sensitive subject, as one man said:

“You have to address death, I mean it’s just like anything else in your life and the more you prepare yourself mentally, and I don’t know whether it’s possible to physically, but mentally I think you would be a winner of some sort.”

In general, we have found that people do accept that suffering and death are part of life, and they are not unwilling to discuss these. In conversation, people noted with regret that because death is now largely hidden in hospitals and aged care facilities, many people do not know how to respond to a person who is dying. People who have had more exposure to death are less afraid of it. One participant noted:

“Whether you are dying or you are dead, you are not part of this society anymore and it becomes something taboo… hiding makes it harder…’

Participants recognised the value of talking openly about the reality of death as a part of life. Our findings suggest that conversations about death need to take place well before a person is ill or dying. Doing so will begin to normalise the place of death in life, so that when it comes people have the structures in place to alleviate suffering – physical, emotional, existential – for the dying and bereaved.

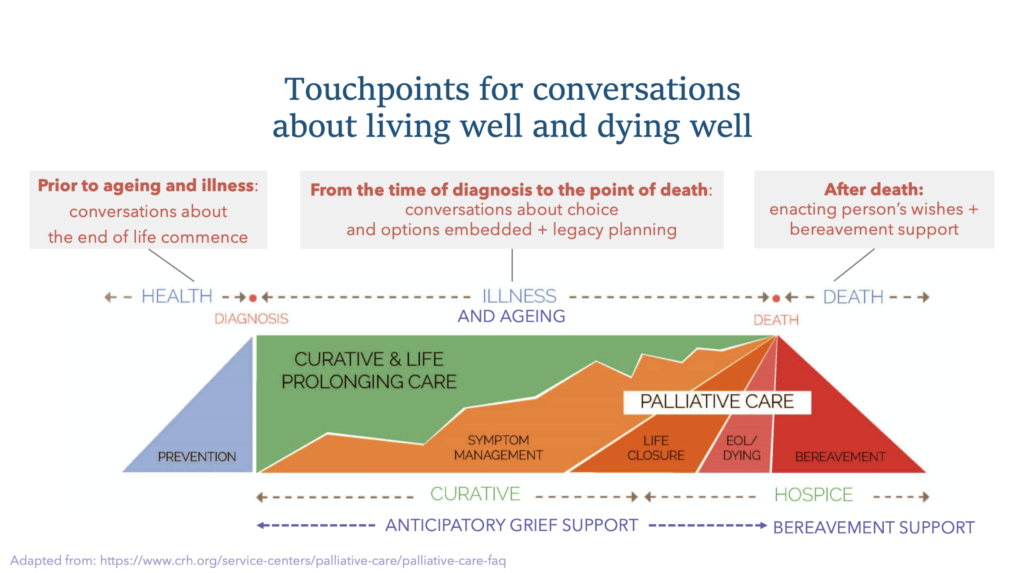

It is notable that not one participant indicated that a care provider had initiated conversations about preparing an advanced care directive or communicating wishes about the end of life. The diagram below was developed by Columbus Regional Health; we have adapted this to indicate the points along the lifespan where conversations around living well and dying well can and should be discussed.

With regard to physical suffering, people identified three main concerns:

1) potential pain and loss of dignity;

2) receiving futile interventions; and

3) maintaining the integrity of the whole person and the body.

Participants do not want to be kept alive unnecessarily and they do want agency in the decision-making process. More than anything, they want to know that they will be cared for in a compassionate and respectful way which honours their lives, wishes and choices. People also expressed concerns about emotional suffering, such as being alone, lingering too long, and leaving children or other loved ones behind.

Some people spoke of spiritual or existential suffering, such as worries about the meaning and purpose of life. Roughly half of the people we spoke with identified with a religious or spiritual tradition, and most indicated that their spiritual beliefs provide a framework for accepting the reality of death as a part of life. Rituals and observances can create structures in which people can find their grief contained and shared.

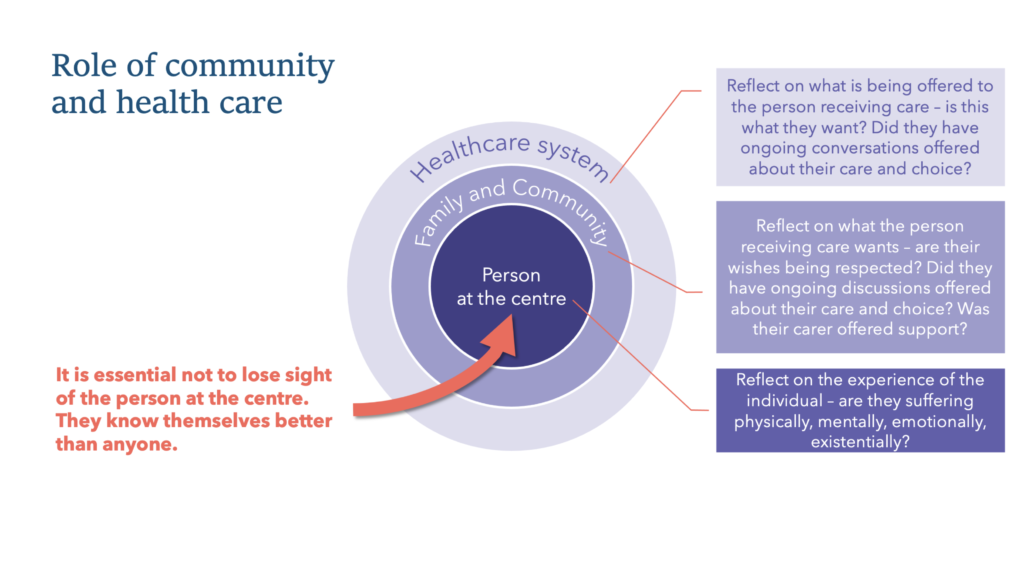

Our research suggests that, although it may be challenging to raise the topic, it is valuable to discuss what is important at the end of life with those we love and trust, so that each of us is informed and prepared, to the extent that we can be, to respond to death when it inevitably comes. There are important roles in this ongoing conversation for not only for health providers but also for community members, families and loved ones, with the individual themselves at the centre. The diagram below illustrates this, along with examples of questions for reflection.

As part of the follow-up to our conversations, we provided each participant with the care companion decision aid tool developed by Queensland Health (currently in draft form), which is designed to facilitate decision-making and truth-telling regarding one’s life and death. There are many other initiatives which also seek to increase the level of death literacy in the community, such as Palliative Care Australia’s discussion starters, the Groundswell Project, or the Commonwealth Government’s resource, My End of Life Care.

Overall, what emerged most clearly from our conversations is recognition that dying is a social process.

It affects not only the person who is at the end of life but everyone around that person as well. For that reason, we need a social response to the suffering that can occur when someone is dying, in addition to any medical responses which may alleviate physical pain or discomfort. Social responses focus on what is important to the individual, including time with loved ones, meaningful conversations, touch, and objects, music or rituals which bring comfort.

The Lancet Commission on the Value of Death identified five principles for a world in which death is valued as a part of life. These include a recognition of the ‘social determinants of death’; understanding death as a ‘relational and spiritual’ process as much as a physical one; and normalising conversations about death and dying.

A number of people told us that as a result of our discussions they have since initiated conversations of their own with family members and loved ones, for instance to communicate their preferences for the end of life. We believe that more open and honest conversations will ultimately ease suffering by helping each of us to prepare for our own deaths and those of others, and will help mitigate social, emotional and spiritual suffering as well as physical. This is summed up by a quote from one of our conversation participants:

“Staring death in the face and really being aware that you could die any moment kind of makes life a bit richer you know, and so there are many benefits to talking about dying, some of which is to make life better right now not just to make death better.”

Linda Kurti

Managing Director

Stillpoint Strategy

Harpreet Kalsi

Head of Health and Healing

Cox Inall Ridgeway